Closed-end funds, in my opinion, are one of the great untapped asset classes of the investing world.

Not many people know about them, not many retail investors take advantage of them, but those who do are often quite successful.

The first step is to start thinking beyond stocks and bonds. Many financial advisors teach us that there are two sides to the investing game: stocks for growth and bonds for safety. And a diversified portfolio should be made up of both, weighted one way or the other depending on how old you are (younger investors should have more stocks, older investors should have more bonds).

And that’s all well and good.

But I’m here to tell you that there’s more to a diversified growth portfolio than just those two types of assets. Closed-end funds are a unique kind of investment that can provide savvy investors with growth- and income-oriented alternative that combines many of the attributes of both stocks and bonds, being especially useful as part of a long-term portfolio.

- Where Did Closed-End Funds Come From?

- How Do Closed-End Funds Differ From Traditional Mutual Funds?

- Why Do I Love Closed-End Funds?

- Let’s Talk About NAV (Net Asset Value)

- Why to Never Buy a Closed-End Fund at Its IPO

- Smart Investors Have Been Using This Strategy for Generations

- Activist Investors: Your New Best Friends

- The CEF Investor’s Toolkit

- Choices and Strategies

- Tying It All Together

First, what is a closed-end fund?

Let’s go right to the source, the Closed-End Fund Association, for the definition:

“Closed-end funds (CEFs) are professionally managed investment companies that offer investors an array of benefits unique in the investment world. While often compared to traditional open-end mutual funds, closed-end funds have many distinguishing features. They offer investors numerous ways to generate capital growth income through portfolio performance, dividends and distributions, and through trades in the marketplace at beneficial prices. CEF shares are listed on securities exchanges and bought and sold in the open market. They typically trade in relation to, but independent of, their underlying net asset values (NAVs). Intra-day trading allows investors to purchase and sell shares of closed-end funds just like the shares of other publicly traded securities. In addition, when shares of closed-end funds trade at prices below their underlying NAVs (at a discount), investors have the opportunity to enhance the return on their investment by making bargain purchases.”

What this all means, then, is that all closed-end funds share three attributes:

- They contain a collection of assets, like stocks, bonds, etc.

- They trade at a price that’s less than what all of those underlying assets are worth (the NAV)

- And they trade on the open market just like normal stocks

They’re a little bit like the traditional mutual funds (referred to in this context as “open-end funds” because they accept investment continually, unlike closed-end funds that only accept investment at launch) that are in your retirement account with one critical difference.

The biggest difference between open- and closed-end funds is that open-end funds are purchased and redeemed through the fund’s sponsor and closed-end funds trade on the open market (like the NYSE).

This difference is critical to my closed-end fund strategy.

But first let’s dive in and discuss this asset class in more depth. Then the strategy will become clear.

Where Did Closed-End Funds Come From?

You may only be hearing about them for the first time right now, but closed-end funds are not a new investment vehicle. In fact, they have been around for hundreds of years.

The first closed-end fund offerings were sold the 1860s in Europe to raise funds for infrastructure projects. According to the Closed End Fund Association, the fund structure found its way to the United States in 1893 as a way to raise funds for projects such as railroad build-outs, and during the big bull market of the 1920s, many new funds were sold to the public.

It was an interesting time for investors.

In that last period of unregulated markets, many of these funds were run by charlatans that used excessive leverage and outrageous speculation to lure the investing public with promises of outsized returns. The fund managers engaged in insider sales of stocks to the fund at inflated prices, misstated closing prices and manipulated prices to inflate the performance figures and fees earned.

In the crash of 1929, many of these funds collapsed and disappeared, taking investors’ money right along with them.

Simply put, closed-end funds did not have a good reputation.

Although the practices that led to disaster were eliminated by passing the Securities Act of 1933, the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 and the Investment Company Act of 1940, closed-end funds were not a popular vehicle on Wall Street for many years to follow.

But that slowly changed, and by the 1980s, big name investors like Marty Zweig (famed growth investor and founder of Zweig Fund, Inc. who was best known for calling the crash of 1987 on Wall Street Week the Friday before it happened), Charles Allmon (growth stock investor and publisher of the Growth Stock Outlook for 43 years) and Mario Gabelli (famous value investor and risk arbitrage trader) figured out that closed-end funds offered an advantage to the firm that put the deal together and managed the assets. Open-end mutual funds were all the rage at the time, but closed-end funds were a potentially better deal for the managers.

Think about it this way:

With a regular open-end mutual fund, if your performance lags or your preferred asset class falls out of favor, investors usually sell their shares in your fund and the fund manager has to send them back their money.

This causes problems for money managers.

It can be difficult to manage money in high-risk or low-liquidity sectors, because the sudden swings in these markets can lead to dramatic sell-offs. For example, biotech stocks are notoriously volatile, so a rapid plunge in the price of a given biotech fund might cause many of the fund’s holders to sell their shares. In order to pay that money back, the manager is contractually obligated to sell stocks and bonds from their portfolio—again, at a low price—to make good on those redemptions. (FYI, this happens anytime you buy or sell shares in a mutual fund, it just causes more difficulty in volatile sectors.)

Closed-end funds don’t have this problem. A closed-end fund is a more permanent source of capital, not an open fund like most mutual funds.

Since shares in closed-end funds are traded on the open market—on stock exchanges like the NYSE and the NASDAQ—an investor who wants out of the fund simply has to sell his shares on the exchange, just like any other stock holding. There are no redemptions for managers to worry about, and no new shares have to be issued to meet a flurry of demand.

The buying and selling of the fund’s shares has no impact on the holdings or balance sheet of the fund. It is permanent capital. Permanent capital is money that cannot be withdrawn once it is accumulated by the investment manager.

This offers a long list of benefits—not only for fund managers, but for the rest of us as well.

How Do Closed-End Funds Differ From Traditional Mutual Funds?

All that said, in truth, they aren’t that different.

Closed-end funds are a type of mutual fund that work a lot like the regular funds. The fund managers gather assets to manage funds just like regular, open-end mutual funds—the ones you are already familiar with and probably own in your retirement plan.

Remember what I said before?

The biggest difference between open- and closed-end funds is the fact that open-end funds are purchased and redeemed through the fund’s sponsor and closed-end funds trade on the exchanges.

And this difference is critical to the closed-end fund investing strategy.

Given that these funds can be traded, a fund’s shares are now subject to the fear and greed cycle that dominates the financial markets. When investors are worried or scared, they will sell their shares—and they are often willing to sell them for less than they are actually worth. As a result, the shares may trade at a discount to the net asset value of the actual fund shares when enough investors sell.

This fact allows us to buy up funds for less than they are worth (but more on that later).

Another key difference between the two is that closed-end funds will often use what is known as a “managed distribution policy” to attract and maintain shareholders. A fund with this type of distribution policy in place will attempt to pay out an even level of income from dividends, interest income and realized short- and long-term capital gains to shareholders. This is also often used as a way to reduce discounts on some funds.

The distribution policy will generally target a fixed percentage of total assets, based on what managers believe the fund will earn over a given period of time. If there is an excess of leftover capital, the fund may raise its payout amount or pay a special dividend to shareholders. If there is a shortfall, then the fund may use a return of capital to meet the targeted return.

For this reason, unless you need the income on a regular basis, it is usually best to reinvest your distributions from closed-end funds while you own them.

Funds have to get an exemption from the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) from Rule 19b-1 of the Investment Company Act of 1940, which prohibits an investment company from distributing realized net long-term capital gains more than once a year—but this is routinely granted for closed-end funds. Getting around the distribution rules allows these funds to sell small amounts of stocks and bonds and distribute the cash on a monthly or quarterly basis to meet the managed distribution guidelines.

Why Do I Love Closed-End Funds?

Closed-end funds are a fantastic example of Mr. Market at work.

This concept was first introduced to us by the great Benjamin Graham in his classic book, “The Intelligent Investor.” As the dean of value investing wrote:

“Imagine that in some private business you own a small share that cost you $1,000. One of your partners, named Mr. Market, is very obliging indeed. Every day he tells you what he thinks your interest is worth and furthermore offers either to buy you out or to sell you an additional interest on that basis. Sometimes his idea of value appears plausible and justified by business developments and prospects as you know them. Often, on the other hand, Mr. Market lets his enthusiasm or his fears run away with him, and the value he proposes seems to you a little short of silly. If you are a prudent investor or a sensible businessman, will you let Mr. Market’s daily communication determine your view of the value of a $1,000 interest in the enterprise? Only in case you agree with him, or in case you want to trade with him. You may be happy to sell out to him when he quotes you a ridiculously high price, and equally happy to buy from him when his price is low. But the rest of the time you will be wiser to form your own ideas of the value of your holdings, based on full reports from the company about its operations and financial position.”

That is the very heart of my closed-end fund strategy.

Let’s Talk About NAV (Net Asset Value)

Net asset value (NAV) is simply a fancy way to say “net worth.” At the end of each day, mutual funds—including closed-end funds—are required to add up the value of the stocks, bonds, cash and any other investment securities they might own. They then subtract anything they might owe like margin debt or expenses that must be paid soon and divide the resulting number by the number of shares outstanding. That number is the net asset value per share.

Let’s go back to the Closed-End Fund Association for the official word:

“Net asset value (NAV), which is the value of all fund assets (less liabilities) divided by the number of shares outstanding, is very important in an open-end mutual fund because it is the price upon which all share purchases and redemptions are calculated. For purchases of mutual funds with front-end sales loads, known as “load funds,” a brokerage charge generally is added to NAV to determine the purchase price. Conversely, closed-end fund shares are bought and sold at ‘market prices’ determined by competitive bidding on exchanges and not at NAV. Let’s assume that the market price is $18 per share and that NAV is $20. In this case, the closed-end fund sells at a discount of $2 per share. On a percentage basis, the fund sells at a discount of 10% ($2 divided by $20). If the market price is above NAV, say $21 in this case, then the closed-end fund sells at a premium of 5%.”

For a variety of reasons, many closed-end funds trade at a discount to NAV. This means that investors can often buy a dollar’s worth of securities for perhaps 95 cents or less. Even when the brokerage commission is added to the purchase price, the investor may be purchasing an interest in underlying securities with a value in excess of the fund’s market price, thanks to the discount.

Think about it this way:

At times, various funds are going to be out of favor and unloved by the market, and their shares will trade at a discount to net asset value. Over time, the asset class will come back into favor and the shares will trade at a lower discount or, sometimes, even a premium to the net asset value.

This discount is where much of the value lies in a closed-end fund. As long as you purchase the fund at a discount, you always know that your investment is worth more than you paid for it.

Let me use a real fund as an example to help give you a better idea of how the discounts on closed-end funds work.

Royce Value Trust (NYSE: RVT) is a closed-end fund run by the Royce Funds, a firm started by well-known value investor Charles Royce in the 1970s. The firm has delivered solid results over the years by investing in smaller companies that it thinks are undervalued and could rise in price.

In 1986, Royce sold shares in the very first small-cap value closed-end fund, the Royce Value Trust. The fund has done pretty well over the 30 years of its existence, with annualized returns of a little better than 10%, versus about 7.57% for the S&P in that time. It’s a good little fund and Charles Royce still manages the portfolio personally today.

In the aftermath of the 2000 Internet bust, small-cap value strategies became very much in favor. All of a sudden, valuation mattered again and investors began flocking to strategies like those practiced by Mr. Royce. Because of his long, successful track record, investors were actually willing to pay a premium to buy shares of his fund. At times they were paying as much as 5% more than the actual value of the stocks, bonds and cash held by the funds. As a result, the fund’s share price soared.

Of course, we eventually ran into another bubble top and all equities went out of favor very quickly. The shares were back to trading under their true value as markets fell quickly between 2007 and 2008.

As we look at the fund today, its shares are trading at discount to net asset value of around 10%. This means that investors today can purchase the fund for less than the total value of the stocks, bonds and cash held in the portfolio.

And this is during a period when value funds in general are not faring very well.

Think about what will happen when investors get excited about small-cap value again, like they did back in 2000. It is highly likely that the fund will go back to its NAV or even above it again. Just eliminating the discount would provide us a 10% return without the stocks and bonds rising by a penny.

Of course, the only thing that will get investors excited about small-cap value again is a recovery for value stocks across the board, so the returns would likely be higher as the NAV itself could be appreciating.

This discount to premium cycle plays out across a wide variety of strategies and asset classes. I have seen this work in growth funds, emerging market funds, high-yield bond funds and yes, even plain, boring old tax-free municipal bond closed-end funds.

Why to Never Buy a Closed-End Fund at Its IPO

Before we delve deeper into the specifics of my strategy, I want to address another source of closed-end fund discounts.

When a firm decides to introduce a new closed-end fund, they do so through an initial public offering (IPO), which is very similar to the process a new company goes through at IPO. The fund managers hire a brokerage firm to help them put the deal to together and sell shares to the public. The lawyers and accountants from the fund and the brokerage firm get together and compile all the information and documents required by the SEC. They also negotiate with the major stock exchanges to select one where the shares will trade after the initial offering to investors is completed. Once the SEC approves the documents and an exchange has agreed to list the shares for sale, the deal is done and the shares can finally be sold to the investors.

But smart investors shouldn’t buy at that point.

As I said, closed-end funds tend to go in and out of favor on Wall Street, and when they are in favor, the sales machine that is Wall Street is delirious with joy. This is because Wall Street has found that these funds are ridiculously easy to sell to investors.

They are especially easy to sell to income investors.

New funds often tout anticipated yields that are above the current rates available on traditional fixed income offerings like bank CDs and treasury bonds. There are no visible fees, as no trading commissions are charged on the IPO.

What a deal!

Unless you actually sit down and read the prospectus (which nobody does), an investor would never realize that there are sales commissions being paid to the broker off the top, as well as underwriting fees being collected by the sponsoring firm. Brokers are getting paid as much as 5% off the top to sell you the fund at its IPO. By the time all the various fees are deducted, you are lucky if 91% of what you pay for the shares actually gets invested on your behalf.

And that anticipated yield? It usually doesn’t start right away either.

The day after the offering fund IPOs, it has piles of cash to put to work, but it could take as long as six months for the dividend yield to reach the level the broker hyped when he was selling it to you.

This is just how the model works. It takes time for a new fund to get invested and for its yield to start rolling. It would have been better to buy an open-end fund or an existing closed-end fund so you could receive the promised yield from day one, but no one is going to tell you that little nugget of information when this much in fees and commissions is at stake.

It never makes sense to buy a closed-end fund at IPO, no matter how much a broker in a great non-commission IPO deal says it is. It is not.

But once all the hype and hoopla surrounding the IPO is over, after the fund has all of its permanent capital, that’s where we find our opportunities. There is no longer a fat new offering commission, so there is no reason for brokers to push the shares. They are going to languish with a few shares trading on the exchange every day, but the big offering push is over. There will be no ads in the Wall Street Journal or on CNBC to encourage investors to buy shares. There are no natural buyers for the shares, so any selling by retail shareholders is going to create a discount, as no one is going to be willing to pay net asset value for the shares.

The shares will be ignored until selling eventually creates a discount large enough to catch the eye of a savvy investor using the closed-end fund strategy.

And that’s where we come in.

Smart Investors Have Been Using This Strategy for Generations

This closed-end fund strategy is not new and has been used by some of Wall Street’s best known investors to begin building or adding to their fortunes.

Well-known activist investor Carl Icahn, for example, opened his shop Icahn Enterprises back in 1975 doing mostly convertible arbitrage and options trading. It wasn’t too long before he and his partner Alfred Kingsley noticed that many publicly traded closed-end funds were trading at large discounts to NAV. They began buying shares of the funds, accumulating a significant stake.

But that was just the beginning.

They would then call on the fund manager at the closed-end fund and demand the shares be liquidated. Icahn got his way quite often since he owned a significant number of shares and could persuade other large shareholders to vote with him in favor of liquidation, and the fund was liquidated at a large profit. Eventually, just the news that he was targeting a fund would bring in new buyers and eliminate the discount, giving him a decent profit.

After several years of using this closed-end fund strategy, Icahn moved on to activist projects against larger operating companies, as the closed-end fund universe back then was nowhere near as large as it is today. But the fact remains that it was the closed-end fund strategy—not too different than what we’re doing here—that launched his decades-long career as a corporate raider and activist investor.

And that is just one example.

There is plenty of evidence that the closed-end fund strategy works very well over time.

Arbitrage shops have used this approach since publicly traded closed-end funds were invented. In fact, Benjamin Graham himself pointed out the wisdom of buying these funds when they trade at a large discount to net asset value.

There are several niche investment firms that use the closed-end fund strategy with a great deal of success. Firms like Bulldog Investors, Western Investment and SABA Capital all use the closed-end fund strategy today to earn solid returns for their investors.

So why doesn’t everyone do it?

The answer is that it is not sexy.

This strategy is about hitting singles and doubles, not mammoth home runs. It is not an active strategy like day trading or some other system that makes your broker rich.

The closed-end fund strategy is designed to build wealth over time the same way the legends of Wall Street like Icahn and Warren Buffett did. You do not have to be a rocket scientist to achieve solid returns with this approach, but you do have to do your homework and use patience and discipline.

Most investors don’t want to make the effort.

But we aren’t most investors. We know that true wealth is built on “small ball” investing like this, and that is why we win.

Activist Investors: Your New Best Friends

Before we move onto specific sectors and how you should consider using the closed-end fund strategy in each, I want to introduce you to your new best friends: the activist investors that make the closed-end fund world go ’round.

Our whole objective as closed-end fund investors is to buy funds with large discounts to net asset value and then sell them when that discount narrows, all the while collecting fat dividends. If we can find a partner with deep pockets to help us achieve that task, then it makes sense to work with them.

In fact, there is such a group and we can often buy alongside these investors and benefit as they use the strength of their much larger positions to narrow or even eliminate the discount on a closed-end fund.

The group I’m talking about are the activist investors who today do exactly what Carl Icahn and Co. were doing back in the 1970s. They identify closed-end funds that are trading at a discount and then pressure management to take steps to close the discount. These steps might include liquidating the fund and returning cash to shareholders, converting the fund to an open-end fund, conducting a buyback or tender offer at or close to the net asset value, or adopting a managed dividend policy that makes the shares more attractive to investors.

Anything to narrow that discount so that the investor can earn a premium on their shares.

The rest of us closed-end fund investors just come along for the ride.

This has been a pretty productive subset of activist investing lately.

A 2008 study by Michael Bradley, Alon Brav, Itay Goldstein and Wei Jiang of Columbia University found that open-ending attempts have a substantial effect on discounts, reducing them, on average, to half of their original level. An open-ending attempt is a move by activists to convert the fund from a closed-end structure to a traditional open-end fund that by law has to trade at net asset value.

The researchers noted:

“We find that activist arbitrage has substantial impact on CEF discounts. While most of the open-ending attempts in our sample were met with resistance from the funds’ managements, quite a few led to successful open-endings despite such resistance. In addition, activists’ activities were sufficiently credible in many instances to induce fund managers to take actions themselves to reduce the size of the discount.”

The activists are basically doing exactly what we are doing with our closed-end fund strategy, and we can track their efforts to help us achieve better returns.

In fact, that’s exactly what we’re going to do.

There are only a handful of investors involved in the closed-end activism space right now. Why? The closed-end fund universe is just not large enough to handle tens of billions of dollars of activist dollars.

If you want to be the biggest kid on the block, you simply will not be able to make closed-end fund activism a major part of your investment strategy. If you are looking for a home run every time up to bat, it is not going to work for you either.

Closed-end fund activism relies on a steady stream of doubles and singles to achieve high returns. I have a friend who is an ardent baseball fan and he refers to closed-end fund activism as Rod Carew investing as opposed to Barry Bonds investing.

But that’s not to say that no one is doing this. There is today a dedicated core of activist investors in the closed-end fund space, and the activists who play this game are experts at their craft.

Bulldog Investors is one of the best known firms in closed-end fund activism. Fund manager Phillip Goldstein came to the investment world after spending the first 25 years of his working life as a civil engineer for New York City. His love of math drew him first to gambling games like blackjack and eventually to the stock market. He quickly discovered the world of closed-end funds and the ebb and flow of discounts and premiums.

He met his eventual partner Steven Samuels at a closed-end fund investing conference and in 1992 the two opened Bulldog Investors with closed-end fund activism as a major part of their investment strategy.

How are they doing?

In interviews, Mr. Goldstein has talked about returns around 15% annually, and using WhaleWisdom.com to check his 13F filings over the past decade, I got results that were around that same level. They have been at least high enough to keep the firm in business for almost 25 years, which is a remarkable achievement in the rough and tumble world of hedge funds.

Art Lipson is another activist who focuses on closed-end funds. His firm, Western Investment, has been involved in activist investing since about 2004. Mr. Lipson himself has been active in closed-end fund investing, primarily on the fixed income side, since the mid-1980s.

Interestingly, in the early part of his career, he developed the first bond indexes and bond index funds while at Kuhn, Loeb & Co., and then Lehman Brothers. The indexes he created are now the Barclays Fixed Income indexes that are widely used to track various fixed income markets.

Since moving out on his own, his firm has been involved in more than 40 closed-end fund activist campaigns with a great deal of success. He has waged battles with Deutsche Bank AG, First Trust, Nuveen and other fund managers and has often been successful in getting funds to convert to open-end or conduct a tender offer close to net asset value.

In his most recent campaigns, he took on Deutsche Multi-Market Income Trust (NYSE: KMM) and Deutsche Strategic Income Trust (NYSE: KST) and helped narrow discounts by about 50% in both cases.

And he’s still feisty.

In a CNBC interview a few years ago, the 71-year-old Lipson said:

“I have a saying about Wall Street guys. They’re driving Mercedes convertibles, lighting cigarettes made out of $100 bills, while I’m on the sidewalk picking up quarters out of a puddle. If the guys on Wall Street are Saks Fifth Avenue, I’ll be Wal-Mart. OK, I’ll be Costco.”

George Karpus founded Karpus Investment Management in 1986 to focus on offering clients conservative, long-term management of their wealth. Along the way, the firm has developed an expertise in using closed-end funds to achieve client goals.

According to its web site:

“Karpus Investment Management has been a major investor in closed-end funds for more than 15 years. In addition to following this market closely, KIM engages in shareholder enhancement to maximize investment returns.”

The fund is pretty low-key and does not look for a lot of publicity, but it does have some great articles on investing in general and closed-end funds specifically on its web site. And it’s good at it. According to Whale Wisdom, they have beaten the market over the last decade with lower volatility.

The CEF Investor’s Toolkit

To get started as a closed-end fund investor, there are a couple important tools you will need.

Associations

The information you are going to need to manage my closed-end fund strategy is easily available today. Web sites like those managed by the Closed-End Fund Association (www.CEFA.com) and CEFConnect (www.CEFConnect.com), provided by Nuveen Closed-End Funds, have all the information you are going to need.

Using these tools, you can quickly and easily search the universe of closed-end funds based on discounts, premiums, total returns and other factors. CEFA also offers a wide range of articles and commentaries by closed-end fund managers and people who invest in this sector to help you stay on top of what is going on in the markets in general and closed-end funds in particular.

Publications

Barron’s publishes a list of closed-end fund prices and their net asset values and current pricing. It even saves you the trouble of figuring out the percentage discount or premium, as it provides that information every Saturday as well. The publication also splits the universe up by fund type, making it pretty easy to read through the tables to look for funds that might be worth buying.

Fund Sites

All of the fund managers themselves have websites where you can get further information, including manager bios and details of the complete portfolios owned by the fund. All provide semiannual and annual reports and some also add quarterly commentary. Of course, discounts and premiums are also tracked daily on these sites.

The Securities and Exchange Commission

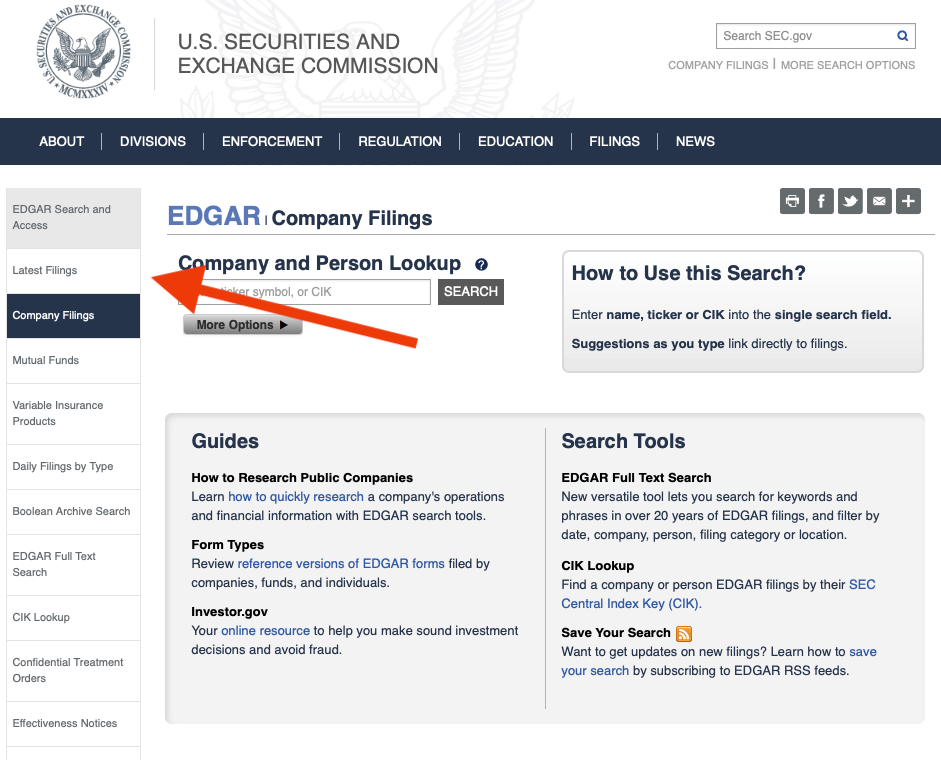

The best way to track closed-end fund activist activity is to go to www.SEC.gov and head to the “company filings” section.

The link is in the upper right corner of the homepage under the search box. Click on the “latest filings” tab on the left side of the page.

When the search form comes up, enter the form number you are looking for. There will be two form types, 13D and 13G, that we want to see, and it is important that you know what they are and the difference between them. (Note: You may need to search for “SC 13D” and “SC 13G”)

I run this search pretty much every day. It is how I stay on top of developing opportunities in the closed-end fund world and ensure that my strategy is working efficiently.

According to the SEC, the Schedule 13D is commonly referred to as a “beneficial ownership report.” The term “beneficial owner” is defined under SEC rules to include any person who directly or indirectly shares voting power or investment power (the power to sell the security) in a particular company. When a person or group acquires beneficial ownership of more than 5% of a voting class of a company’s equity securities, registered under Section 12 of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, they are required to file a Schedule 13D with the SEC.

When an activist acquires more than 5% of the shares of a fund, they have to file this report, outline how many shares they purchased and give a reason for why they bought them. The usual reason is that the buyer thinks the shares are undervalued and intends to benefit from the long-term appreciation, or some language of that matter, but when you read the filing it is important to read this part, which is Section 4 of the SC 13D filing.

The second form I search for every day is SEC form 13G. This form is used when a buyer in a particular security has a passive interest only and has no intention to taking a proactive or activist approach. The buyer must own between 5% and 20% of a company or fund to use a 13G. If they buy over 20%, they must file a 13D.

The 13D carries more weight for our purposes, but even a 13G indicates that the buyer is willing to own a significant amount of the fund at current prices, so the target must be investigated.

These filing searches turn up a lot of filings that are 13D/A or 13G/A. These are amended reports. They can indicate that a buyer has added to their position, but they can also be used to report that they have been selling and now own less than 5%. They are also used to report interaction or correspondence with management.

An amended report that shows buying or an initial 13D or 13G filing means that we can move to analyzing the fund based on its sector or asset class. I am going to lay this process out for you in the next section.

The closed-end fund strategy works just fine on its own, as reversion to the mean is a powerful force when it comes to fund discounts and premiums, but having activist and institutional involvement just gives us a little turbocharge. These SEC filings are how I identify and track them.

Choices and Strategies

One of the really attractive things about the closed-end fund strategy is that there are lots of different funds out there and they invest in different assets, sectors and strategies.

Most of the time, we can find funds that are out of favor and trading at substantial discounts. Eventually the asset class or sector comes back into favor and the discount will shrink or go away entirely, giving us a decent profit.

Of course, when the fund becomes popular again, it almost always means that prices are rising, so we get the double whammy of the discount closing while the net asset value is rising.

Let’s look at all the various alternatives available to us in the closed-end fund universe and talk about the best strategy for trading each of them.

Tax-Free Municipal Bond Funds

This is my favorite type of closed-end fund to trade.

Municipal bonds are issued by cities and states around the United States and the great thing is they tend to pay their bills even in the most difficult times. Municipalities have the ability to raise taxes and charge fees to raise the money to pay their interest and principal payments, and there is a huge appetite for tax-free bonds from institutions and high net worth individuals, so there usually is not much trouble rolling them over or extending maturities to delay full repayment. Even when a municipality does file a bankruptcy—like Orange County, California did back in 1994, and Detroit in more recent years—everyone ends up getting paid back in full.

Rich people love municipal bonds.

I remember when Ross Perot ran for president back in 1992. He was, of course, a super-rich guy and he had to file the same financial disclosure forms as everybody else who was running for office, disclosing what he owned and owed. While he had a little bit of money in the stock market, almost all of his money was in tax-free municipal bonds.

Why? He was already rich so he didn’t need to take a bunch of risk. Tax-free municipal bonds were safe and paid regular interest that was exempt from state and federal income taxes.

I like to tell the story about an email that showed up in my inbox one day by mistake (how that even happened is an entirely different story). It was for a well-known investor from his broker and listed his portfolio. If you were looking for stock tips from this person’s portfolio, you were out of luck. All of his money was in tax-free municipal bonds.

My point is, rich people love municipal bonds and so should you, especially since we’re going to be buying them at a discount using my closed-end fund strategy.

There are two ways to implement the tax-free closed-end fund strategy.

My favorite is to wait for a state or municipality to fall wildly out of favor with investors due to fiscal problems. The doom-and-gloom media will be all over it and begin to predict that the affiliated municipal bonds will go into default and investors will lose billions because they bought the bonds. This will scare the pants off the retail investors who own closed-end funds that have a lot of that municipality’s bonds, and they will sell with little regard for either price or value.

The period of 2009-2010 was a great example of muni bond panic, and California is the poster child for this strategy. That makes sense, since California is famous for its budget problems and high tax rates.

In those days, the TV was full of sober-looking folks telling investors that their California municipal bonds would be worthless.

Part of it made sense.

California does have high income taxes, and because of that, there has always been huge demand for the state’s tax-free bonds. Residents who owned California tax-free bonds paid neither federal or state income taxes on the interest payments, so before the credit crisis, they were very much in demand. Wall Street saw the demand as a huge opportunity to make big commissions and began developing and selling California-specific tax-free bond funds. They sold tens of billions of dollars’ worth of California closed-end funds, collecting as much as a 5% commission on every dollar they took in.

That ended pretty quickly once the doomsday machine got started on the “California collapse” story.

Indiscriminate panicked selling of closed-end funds caused these funds to trade at huge discounts to net asset value. The Nuveen California Dividend Advantage Municipal Fund 3 (NYSE: NZH) traded at a discount of over 15% to the value of the underlying bonds. The discount on the MFS California Municipal Fund (NYSE: CCA) was over 20%. Some of the fund yields reached double digits completely tax-free.

Guess what happened?

Nothing.

California is the largest economy in the United States and if it was a stand-alone nation it would be the seventh largest in the world. While state and local officials have a well-deserved reputation for goofiness, they were never going to let the state fall off a fiscal cliff and default on its bonds.

Once they figured things out and got back on track, investors began to realize that the collapse was not going to happen and they piled back into the funds and the discount evaporated. Those savvy folks who realized that California is actually a pretty prosperous state made an enormous amount of money.

I call this part of the tax-free strategy my “bear market end of the world tax-free approach.”

We are not seeing any full-blown panics to exploit right now, but we will eventually and when we do, I will steer us into the right funds at huge discounts so we can reap the rewards. There are rumblings every day about states like Michigan, Illinois, West Virginia and Oklahoma experiencing financial difficulties. Eventually the doom-and-gloom machine will seize one of them and create a big opportunity for us.

The bear market end of the world strategy can work with national tax-free funds as well. We saw that in late 2015 when there was talk of interest rate hikes by the Federal Reserve and we saw some panic selling of tax-free closed-end funds as investors feared that higher rates would mean lower bond prices. Lots of funds traded with double-digit discounts to NAV.

Of course, then we had a string of weak economic numbers, and Brexit happened, and bond prices rallied. The average closed-end muni fund discount today is about 1% and many of them trade at a premium.

The second tax-free closed-end fund strategy is just my run-of-the-mill everyday tax-free strategy.

There is a reason rich people like tax-free funds. If you are in the top federal bracket, a 4.5% tax-free interest rate is like getting a yield of over 8% since you do not have to pay taxes on the money. To get over 8% right now, you would have to own the junkiest junk bonds with huge risks.

Tax-free bonds, however, are backed by the taxing and revenue generating abilities of states, cities, counties and towns around the United States and are much safer than junk bonds. With rates where they are now, the after tax yield on a municipal bond is 5 to 10 times higher than you get on saving accounts, CDs, money market accounts, treasuries or savings accounts. We have little to no credit risk and can just collect the regular interest payments, spending them if you need income or reinvesting them each month or quarter if you are still growing your nest egg.

This is the point where I usually get asked about interest rate risk.

It is a fact that the value of the bonds in the portfolio will go down if interest rates were to jump up all of a sudden. We may see some pressure from fears of a fed rate hike but it will be short-lived.

Everybody worries about what is in the Fed minutes, dissecting every word and even worrying about punctuation placement, but the most important phrase in the Fed minutes is one that has been in there for some time. The minutes reflect that:

“The Committee expects that economic conditions will evolve in a manner that will warrant only gradual increases in the federal funds rate; the federal funds rate is likely to remain, for some time, below levels that are expected to prevail in the longer run.”

The economy is doing OK, but it is not doing great at this point in time. Rate hikes will happen slowly and we will have plenty of time to adjust our tax-free closed-end fund holdings.

Of course, if discounts reach double digits, we will simply buy lots more tax-free closed-end funds!

We are still going to focus on discount levels. Even in the run-of-the-mill everyday strategy, I want to buy these funds with above-average discounts.

With the average fund trading at about a 15% discount, that is not hard to do and we can still find funds with decent yields with 6-8% discounts right now. I am not going to back up the truck the way I would if there was a muni market crisis, but owning a few low-risk, highly liquid funds with decent after-tax yields is the closed-end fund strategy equivalent of holding cash reserves. Most of the time, I will have a few high quality discounted tax-free funds in my portfolio.

Core Equity Funds

These are just the regular stock-picking mutual funds that are closed-end instead of open-end funds.

There a bunch of these funds to pick from, including some run by pretty well-known investors like Charles Royce and Mario Gabelli. There are funds like the General American Investors Co. Inc. (NYSE: GAM) and Tri-Continental Corporation (NYSE: TY) that have been around since the 1920s.

There are growth funds, value funds, growth and income funds—pretty much whatever you want when it comes to what the Closed-End Fund Association calls “core equity offerings.”

Most of the time we will, with rare exception, ignore these funds.

Why?

If we wanted equity exposure, there are thousands of open-end funds and ETFs to choose from to achieve our goals, so just buying a run-of-the-mill closed-end fund that is not trading at a huge discount doesn’t make much sense for us. I would rather invest in game-changing technologies and the important trends shaping the world than hold an average, open-end mutual fund of any type.

There is, of course, an exception to this.

I call it the Richard Rainwater approach to investing in closed-end equity funds.

Rainwater was the investor who trained under the famed Bass brothers down in Texas and went on to build a fortune buying up undervalued and depressed assets in energy and healthcare that he later sold for a huge profit.

Rainwater was once asked the secret of his incredible success as an investor and he replied, “Most people invest and then sit around worrying what the next blowup will be, I do the opposite. I wait for the blowup, then invest.”

That is exactly how I approach closed-end equity funds.

When markets collapse, people panic. They shouldn’t, but they do. Their lizard brain flight-or-fight instinct kicks in and they choose flight at a huge rate of speed.

Every time we get a bear market, people sell like the world is going to end, in spite of all the evidence that they should be buying, not selling. The world is probably not going to end, and in the unlikely event that civilization as we know it collapses, I can promise you that you will not give two craps about the price of your stock holdings. Even so, when markets pull back, people panic and they sell.

When they do, we will be there ready and waiting to take advantage of their mistake.

Let’s take a look at this in action.

General American Investors (NYSE: GAM) is one of the oldest closed-end funds in the world. The shares began trading on February 1, 1927 and have been continually trading ever since.

According to the fund’s investment policy, the fund seeks, “investments worldwide in leading public and private companies with significant long-term opportunities, defensible competitive advantages, prudent and profitable business models, and committed first-class management teams with the vision and energy to succeed.”

That translates to some large cap blue chip stocks like Microsoft (Nasdaq: MSFT), Gilead (Nasdaq: GILD), Republic Services (NYSE: RSG) and Cisco Systems (Nasdaq: CSCO) right now.

I went back and looked at their holdings back at the end of the first quarter of 2009. They owned a lot of Boeing (NYSE: BA), Pepsi (NYSE: PEP), Cisco, Berkshire Hathaway (NYSE: BRK.A) and American Express (NYSE: AXP). These were all solid blue chip companies that had all fallen during the market collapse and were down 30%, 40%, 50% and more as we were at the bear market bottom. In spite of this already bargain pricing, thanks to panic selling by its largely retail shareholder base, shares of General American reached a discount to NAV of over 24%.

Investors at that time were getting almost 25% off of what turned to be a seven-year low in stock prices.

As markets began to stabilize, the prices of the stocks held by the fund rose and the discount narrowed somewhat. Over the next year, the fund doubled in price, giving those using a Richard Rainwater equity fund strategy a huge gain in a short period of time.

Bam!

It worked even better for the Gabelli Equity Trust (NYSE: GAB) managed by famed mutual fund manager and value investor Mario Gabelli. It went to a double-digit discount during the bear market, but the comeback was breathtaking.

By the middle of 2009, the fund had doubled in price, and by the end of 2010, those investors employing the Richard Rainwater closed-end fund strategy had seen their shares triple in value. Using the Gabelli fund to execute the Rainwater strategy is a great example of my personal investing rule #1: always invest with somebody smarter than you.

Most of the time, we will only be buyers of closed-end equity funds in really bad markets. We are not going to be lifetime holders of these shares either. When the discounts return to normal or go to a premium, we will take out profits and move on.

There are exceptions to this rule—one notable one we will talk about later—but for the most part, we are bear market buyers and sellers when things stabilize. As I’ve said before, mutual funds don’t outperform the general market, so we only buy extremes with the Rainwater strategy and sell when things return to normal.

Sector Funds

The closed-end fund strategy does give us a chance to exploit sectors of the market as well.

Sometimes different parts of the market will blow up even as the overall market is marching along in a positive fashion. I have seen it over the years with banks, utilities, energy, foreign stocks, emerging markets, gold stocks, and healthcare. There is one or more closed-end fund for all of these sectors, as well as single-country and global regional closed-end funds to allow us to take advantage of regional market disruptions.

I am a big fan of the single-country and regional funds because we get localized market meltdown all over the world and regions can often fall to steep discounts to the rest of the world. When that happens, folks’ lizard brains kick in again and they sell in a panic and closed-end funds specializing in that region or country will fall to huge discounts.

There are country funds for Ireland, Switzerland, China, Japan, Taiwan, Germany, Mexico, Korea, India, Chile and Australia. We will employ the same Richard Rainwater closed-end fund strategy that we do with U.S. stocks to take advantage of severe market dislocations that create big discounts to net asset value.

We can also use the same strategy with sector funds that focus on the Caribbean, Europe, Asia and Latin America. Different regions of the world can experience difficulties that create market turmoil and we can use our closed-end fund strategy to take advantage of it.

The key to sector and regional funds is exactly the same as it is here at home. We want to wait for a market where everyone is scared and the only ones buying stock are not talking to the media.

I define a bear market as one where the market is down about 30% and at least one major media outlet is predicting the end of capitalism.

It will be the same for sector funds.

When we hear about the end of banking as we know it, or the end of fossil fuel usage forever, then it is time to get involved in closed-end funds specializing in that sector. When the pundits all agree that Latin America is never going to emerge and will be an economic backwater forever, it is time to consider funds that invest in that region. Generally speaking, I am not a fan of precious metals investing, but when the news is talking about the permanent loss of metals, it is time to buy precious metals funds.

We will buy heavily discounted funds in really bad markets and take our gains when things return to normal.

Core Fixed Income

These are just basic fixed income funds and include things like government bond funds and high quality corporate mortgage-backed securities.

From time to time, we will get selloffs related to interest rates and economic concerns and discounts on these funds will drift over 10%. It makes sense to buy them when they reach that level.

These are a favorite of banks and other financial institutions looking to earn higher yields in their security portfolios, and sometimes their buying and selling will widen and narrow discounts. We will often to be able to take advantage of temporary widening.

Again, the strategy is about looking for singles and doubles rather than home runs, but it all adds up to solid long-term returns.

High-Yield Bonds

This is another sector that investors should pay the most attention to when the markets are being shredded.

High-yield, or junk bonds, are one of Wall Street’s most volatile and potentially risky sectors, but income-oriented investors have flocked to high-yield bonds since Michael Milken invented the new issue high-yield market back in the 1980s. Since then, the high-yield market has had some spectacular blow-ups that cost uninformed retail investors dearly but created a huge opportunity for those ready to take the other side of a quickly collapsing market.

Wall Street’s marketing pitch for high-yield funds is pretty straightforward. If you own a diversified portfolio of higher risk bonds, you spread out the default risk and earn a much higher return. It is exactly the same concept that Michael Milken worked out when he was a young analyst with Drexel Burnham.

What they don’t tell you is that the returns are achieved over time and it can be an incredibly bumpy ride!

When the economy is weak and the young, riskier companies are having a hard time paying their bills, default rates will skyrocket and high-yield bonds take a beating. The good years are good for high-yield bonds but the bad years are truly horrific.

The retail holders of closed-end funds did not sign up for the horrific part of the deals and when it happens, they have a long history of selling quickly and with no attention at all to the relationship between price and net asset value. In 2008, when credit markets locked up, many of the funds had discounts to NAV of over 20% and those bold buyers that emerged had spectacular returns in 2009 and 2010, with many funds doubling in value over that time period.

My general rule of thumb is to not even be interested in high-yield bond funds until we have a whiff of napalm in the morning surrounding the markets and we can buy funds with discounts of more than 15%.

We had a little mini opportunity in high-yield funds last year when jittery markets and concerns of a rate hike spooked the markets and some funds like the Pacholder High Yield Fund (NYSE: PHF) and the Blackrock Corporate High Yield Fund (NYSE: HYT) fell to discounts of over 15% for a brief period of time.

Now, a year later, those funds have rebounded with returns of around 20% for the year, way in excess of what most stock investors have been able to earn on their investments!

When the sun is shining and everybody loves the high-yield bond market, I want nothing to do with them. They will be priced to perfection and the closed-end funds will have little or no discount to net asset value. All the good news is reflected in the price and the only surprises are going to be bad ones.

While I hate the idea of buying funds when they fall to a huge discount from retail investors who have lost a ton of money, I could not stop them from doing so no matter what I do, so I am prepared to buy their heavily discounted funds when they are desperate to sell at any price.

Yield-seeking investors have been making the same fear- and greed-driven mistakes since someone thought up the idea of markets and investing, and we can exploit that to make piles of money using the closed-end fund strategy.

Real Estate

Most people do not own enough real estate. I know that sounds strange coming from a guy who said that he would rather be shot in the head than buy another house, but it’s true.

The fact of the matter is that real estate is going to go up over time and people will need houses and apartments to live in, office buildings to work in, shopping centers to buy things at, and real estate demand will grow right along with the population.

My reasons for not owning a home have more to do with being trapped in one place and dealing with maintenance all the time than anything else. I can buy real estate via Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs) and get all the benefits of real estate appreciation without ever having to mow a lawn.

I like that.

Thanks to the wonderful world of closed-end funds, I can buy my real estate at a discount to what everyone else is paying, and benefit from the underlying demand for real estate as the mean reversion of the discount!

What most people do not realize is that REITs actually make you more money than stocks most of the time. Since their creation in 1972, equity REITs have outperformed the S&P 500 over just about every time period. According to the National Association of Real Estate Investment Trusts (NAREIT), over the past 20 years REITs have returned 11.33% on average while the S&P has earned an average rate of return of just 9.85%.

Even better that that, they do so with less risk, according to a report NAREIT economist Brad Case published recently. Since 1990, REITs have done much better than the overall market and taken a lot less risk to achieve the returns. A lot of the return from REITs comes from dividends, and that helps prop them up in bad markets.

In the lost decade of 2001-2010, when stock investors actually lost about 1% a year, REITs were pretty volatile, but they actually made money.

A 2010 Forbes article pointed this out, saying:

“Though it was a roller-coaster, the last 10 years saw REITs return around 10% annually compared with the S&P 500′s decline of 1% a year over the same period. REITs returned the same 10% a year over the past 15, 20 and 25 years, showing rather remarkable consistency.”

NAREIT’s numbers show that in the 40-year period ending at the end of 2014, REITs averaged 12.83%, compared to U.S. large-cap stock returns of 12.19%, and they were a lot smoother along the journey than stocks. While everybody got blasted in the financial crisis, if we look back at the blow-up of the Internet bubble, REITs only had one losing year as stocks plunged, and that was by about 2%.

REITs offer better returns than stocks with less risk and we want to own them for the long run.

There are a bunch of REIT closed-end funds available to us and we will own lots of them over the years. It is simply a matter of buying those with the biggest discounts and holding on until the discount for that particular fund is eliminated.

Closed-end fund activists have been buyers in the sector, and we saw Bulldog Investors go after LMP Real Estate Income Fund (NYSE: RIT) and force a merger with an open-end fund run by the same manager to eliminate the discount.

I think we will see a lot more activist activity in REIT closed-end funds and we will be in good shape to take advantage of it when it occurs.

Using the closed-end fund strategy with REIT funds gives us the best possible situation. We own securities that have a long history of outperforming stock with less risk, and we can buy them at much better prices than other investors.

Global Income Funds

These will serve our purposes much like country and regional equity funds do.

From time to time, there will be a blow-up somewhere in the world, be it a single country or a whole region, and we can use global income funds to take advantage of it. They really are something of an “only in a crisis” opportunity along the lines of equity and high-yield funds.

If we look at the history of the Templeton Global Income (NYSE: GIM)—if we are going to invest globally why not use the folks who pretty much invented the idea—we see that the discount level exceeded 15% in the Internet crash, in 2008, and last year when fears of global slowdown along with a rotten geopolitical outlook caused investors to flee anything outside the U.S. In the two-year period following the 2000 sell-off, the fund gained more than 70%. And following the 2008 debacle, the two-year gain was in excess of 80%. We are up almost 7% from last year’s lows.

While that is not spectacular, it does compare nicely with the S&P 500 return over the same period.

Global income funds are another tool to use our closed-end fund strategy to take advantage of the volatility in global markets and exploit short-term market panics for our personal gain.

Senior Loan Funds

These funds have become a staple of the closed-end fund strategy, as they serve as a great place to earn high returns using the expertise of the world’s best private equity managers.

The loans these funds own are the highest in the borrowers’ capital structure and get paid back first in the event of a default. Most of them are floating rate so if rates go up, so does the interest charged on the loan.

The major risk for these funds is credit risk, and no one understands credit risk better than private equity funds.

Private equity funds didn’t invent leverage, but they have pretty much perfected the use of it to fund and grow businesses and make deals. This is an area that banks have pulled away from in the aftermath of the credit meltdown and the increased regulatory scrutiny they now face.

Tony James, the COO of private equity giant Blackstone (NYSE: BX), described what he thinks is happening with senior loan markets on a recent conference call:

“I basically think credit markets are going to be a really, really great place to be going forward thanks to the regulators in the government that are impairing the banks and the investment banks and the providers of traditional writers of liquidity. So very broadly, this is a play where we’re benefiting from regulatory, arguably, overreach.”

In addition to Blackstone, Apollo Global Management and Kohlberg Kravis Roberts have funds that invest in senior loans. Marc Lasry runs Avenue Capital, one of the leading distressed debt funds, and he also has a fund specializing in senior loans. Ares Management is a leading alternative asset manager and it has a fund as well.

These guys understand leveraged lending and we can use senior loan funds to put their expertise to work for us at a discount.

Commodity, Metals and Natural Resources Funds

I am not a huge fan of trying to time tops and bottoms in the commodities market because I just don’t think most people can do it. However, if we let discounts drive our decisions, we can use closed-end funds to take advantage in big selloffs in oil and gas.

I am really not a fan of precious metals, since they, especially gold, are basically just rocks that produce no cash flows, but at times, the share price of some precious metals funds will trade far below the quote value of the shares they own. In these situations, we have to take advantage of the mean reversion trends of closed-end funds.

We won’t use them often but at extremes we will use them to take advantage of the abnormally large discounts to NAV.

A classic example of the extremes I am talking about happened early this year when oil went below $30. I had no idea where oil prices might reach. The oil minister of Saudi Arabia probably wouldn’t have taken my calls if I had wanted to try calling him, and he is the only person who knew what his strategy was going to be in the months ahead.

What I did know was the price of the MLPs (master limited partnerships) that own pipelines and storage plants for oil and gas had fallen by 50% or more as falling prices led to dividend cuts.

Wall Street had once again taken income investors down the primrose path with promises that the pipelines and storage facilities would collect the same income for usage no matter where the price of oil and gas went and dividends could only go up. When instead they went down along with oil prices, investors naturally panicked and sold like crazy.

There were several closed-end funds that invested in the MLPs and they got dumped as well. Many of them were trading at discounts of 20% to a portfolio of MLPs that were themselves already down 50% to 70%.

While the future of energy may be alternative and renewables, that future is not here yet and won’t be for a few decades at least. I may not have known where oil prices were going to go, but I did know that we were going to have to pump and store oil and gas in the future and these pipelines and facilities would be needed.

Furthermore, thanks to our nation’s case of NIMBY (not in my backyard), many of them are virtually irreplaceable. They had real value that was more than the current share price and by using closed-end funds I could get them at an even bigger discount to what they were worth.

As oil prices recovered, so did MLP prices and the discounts narrowed somewhat, combining for a pretty big total return in less than year.

Natural resources and commodities funds are available to us to use as part of our closed-end fund strategy and we will use them in the case of extreme events. We will not use them often, but like a seldom-used but crucial tool, they are in the box if we need them.

Tying It All Together

The core of my closed-end fund strategy, the day-to-day bread and butter if you will, is going to be taking advantage of the expertise of the best closed-end fund investors in the world and riding their coattails to double-digit returns via their 13D and 13G filings.

In the case of 13Ds, we want to allow their activist activity to force management into taking some action to in turn force the discount out of existence. We want to buy as close to their entry point as possible and let them do the heavy lifting for us.

This is not home run investing most of the time. It is just hitting single after single with a few doubles and triples thrown in that allow investors to earn double-digit returns from a fairly low-risk approach to investing.

- Dividends: Most of the funds you should buy will pay generous dividends while we hold them, some of them on a monthly basis, which you can either take in cash or reinvest into additional shares of the fund.

- Tax-Advantaged: Use the regular run of the mill tax-free strategy to earn low-risk, high after-task returns by buying discounted closed-end funds that have discounts larger than the average fund at any given moment in time. Focus on those funds that have solid credit portfolios stuffed full of loans issued by municipal and state governments that can easily pay back.

- Fear: When the doom-and-gloom crowd targets a particular state or the markets are hit with a wave of interest rate fears, employ the bear market end of the world tax-free closed-end fund strategy. When we have lots of funds trading at double-digit discounts to net asset value, load the proverbial boat with tax-free closed-end funds. You should be able to earn high teens returns from the storm tax-free and the eventual closing of the discount from what is in reality a fairly low-risk investment vehicle.

When we have strong market sell-off and there is widespread selling in stocks, employ the Richard Rainwater closed-end fund strategy and buy deeply discounted funds that own stocks.

Here it will make sense to check the portfolio holding before hitting the “buy” button. Make sure you are comfortable with the type of stocks the fund owns before you buy. There will be a difference between a discounted collection of blue chips and a fund with the same discount that owns small biotechs and other risky securities. Use the same strategy on sector funds when a sector of the market blows up for one reason or another and the closed-end sector funds trade at a substantial discount to the underlying securities.

On a global basis you can track the single country and regional funds to locate those where local conditions have created large discounts to net asset value and buy those that are available.

Then it simply becomes a matter of holding until conditions reverse and investors begin to pile back in and eliminate or narrow the discount.

One of the most exciting parts of the closed-end fund strategy is that it gives us a chance to own real estate investment trusts at discounts to their net asset value. REITs have outperformed stocks over time and done so with less risk, according to NAREIT, and most investors do not own enough of them.

I really have no interest in owning another house but I do like the idea of owning apartments, single-family rental homes, office buildings, shopping centers, data centers, warehouse space, and other properties that will benefit from a growing population and rapidly changing world. The closed-end fund strategy gives us a chance to own properties all over the world at a great price.

We will also be able to use the expertise of private equity and credit hedge fund managers to earn high returns in the senior loan market. We will be executing the same direct lending strategies these funds use to generate high returns for themselves and for clients, but we will be doing so at a discount to net asset value, giving us a real chance for even higher returns when discounts narrow.

The closed-end fund strategy works under just about all market conditions.

It should help you earn solid returns, protect your capital in normal times and provide extraordinary opportunities for high returns in bad markets.

It is business-like investing that is based entirely on the fact that fear and greed cycles give us clear entry points based on discounts, sell levels based on the narrowing of the discount, and even the ability to sell assets at a premium to their underlying value.

And I am very excited to share this unique investing approach with you.